Small Planet Communications, Inc. + 15 Union Street, Lawrence, MA 01840 + (978) 794-2201 + Contact

Read the Articles of Confederation

of the United Colonies.

See "A Map of New England,

being the first that ever was here

cut" to learn more about the region

during King Philip's War.

Read more about King Philip's War.

Follow the link to read about the reasons, events, and political and economic aftermath of the war.

At the 1621 feast of thanks in Plymouth, Wampanoag chief Massasoit was an honored guest of the Pilgrims, who were grateful for his tribe's help in the colony's struggle for food, shelter and survival. Relations soon worsened, however, and a little more than 50 years later, in 1676, colonial troops paraded the severed head of his son Philip as a war trophy through the streets of Plymouth—the town his father had saved from starvation. His skull was displayed on a pole for years afterwards. His corpse was cut into quarters, the pieces distributed to different colonies. His wife and son were sold into West Indian slavery.

The war lasted only 14 months, but it nearly destroyed Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Rhode Island—and exterminated the tribes of southern New England. Some 13 New England towns were destroyed and 52 damaged, out of 90 white settlements. English expansion into New England was halted for the next 50 years. Nearly 3,000 settlers were killed. Measured against the total European population of New England, this death rate was twice that of the Civil War and seven times more deadly than World War II. More than 1,200 homes were destroyed, 8,000 cattle were slaughtered, and countless crops and food supplies wiped out.

The New England colonies were made nearly destitute by the costs of the war. The English would survive, however, and they proceeded to hunt down and wipe out tribal culture and village life from southern New England. American Indian battle casualties were eclipsed by deaths from starvation, disease, and exposure. Surviving American Indians across New England were captured and executed. Many captives were sold into West Indian slavery for profit. Even the Praying Indians, who had converted to Christianity and had helped the colonial forces defeat Philip's forces, were sent for a time to an internment camp on Deer Island in Boston Harbor. Many of them died due to the poor conditions before the group was allowed to return to the mainland at the end of the war.

How did goodwill and tolerance dissolve into hatred and revenge? What triggered the uprising of Wampanoags, Nipmucks, and Narragansetts that threatened to send settlers fleeing to England? And what caused the brutal backlash by the English that nearly exterminated the New England tribes?

In 1643 after the Pequot War, a confederation known as the United Colonies of New England was formed in part for the mutual security against any American Indian uprising. It was comprised of the colonies of Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Haven (which later merged with Connecticut), and Plymouth. (Rhode Island would join much later.) The New Englanders mistakenly thought they were well prepared to defend their settlements.

In 1675, the Algonquian Indians all over southern New England attacked the Puritan colonists. The resulting series of raids and skirmishes which raged through the towns and villages of New England over the next year became known as King Philip's War—one of the bloodiest wars in American history.

Read an online book — Soldiers in

King Philip's War, Being A Critical

Account of that War with a Concise

History of the Indian Wars of New

England From 1620-1677. It includes

official lists of soldiers, biographies

of some of the officers, copies of

documents, and more.

The conflict was the result of population pressure on the native peoples immediately to the west and north, notably the Wampanoags, Narragansetts, Mohegans, Poducks, and Nipmucks. The native peoples were upset with the white settlers' livestock that strayed into their fields and trampled their crops. Their economies were destroyed as the game was driven away and the fur trade ceased, and they went into debt as the steady succession of land sales created a growing dependence on English goods. Missionaries like John Eliot tried to preserve the culture of the American Indians, but the underlying pressure to conform to the ways of the settlers threatened to destroy the cultures of the various tribes. Before his death, Massasoit, the Wampanoag sachem who had befriended the Pilgrims, petitioned the Plymouth General Court to give English names to his two sons. The eldest Wamsutta was renamed Alexander, and his younger brother Metacomet—also known as Metacom or Pometacom—became Philip.

DID YOU KNOW?

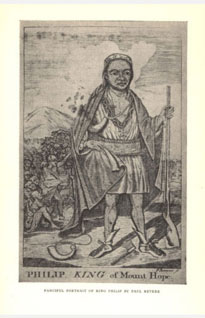

There is no known portrait of

Metacomet, or King Philip, but

his likeness has been depicted in

in various ways. The image above

was drawn by Paul Revere in an era

when American Indians were still

viewed as hostile.

After Massasoit's death, Alexander became grand sachem of the main Wampanoag village, Pokanoket. In the early 1660s, Plymouth officials heard rumors that the Wampanoags had sold land to the white colonists of Rhode Island. It was their contention that treaties between Plymouth and the Wampanoag gave their colony exclusive rights to any land the tribe might be willing to give up. The colony's government brought Alexander to Plymouth for interrogation, after which Alexander became ill and died. Some believe he was poisoned. The following year, Metacomet, or Philip, succeeded his brother as grand sachem.

Alexander's widow, Weetamoo, soon became the sachem of the Wampanoag town of Pocasset, a position of authority that placed over 300 warriors under her guidance and thus made her a political power in her own right. Weetamoo was not only the widow of Philip's brother, Alexander, but Philip's wife was her sister, Wootonekanuske. During the next ten years, as Alexander's successor Philip tried to accommodate English demands, Weetamoo and her soldiers kept the peace.

Read a brief biography of

Governor Josiah Winslow.

In February 1675, the body of John Sassamon was found at Assawompset Pond near Namasket, the Christian Indian town where he had served as minister. Sassamon was an American Indian who had once served as Philip's secretary. He eventually left to teach American Indians near Middleborough, and, shortly before his death, had met with Governor Josiah Winslow to warn that Philip "was Indeavouring to engage all the Sachems round about in a war." Sassamon told Winslow he believed his life was in danger—that Philip would surely murder him if his betrayal was discovered.

Many colonists probably believed that Philip was behind the murder, though others wondered whether Sassamon had been murdered at all and had not simply drowned. In June, a trio of American Indians—Tobias, his son Wampapaquan, and Mattashunannamo—were brought to trial for the murder of Sassamon. Due to the unusual circumstances, the Plymouth authorities added six "of the most indifferentest, gravest, and sage Indians" to the usual jury, and all six of these concurred with the verdict, which was that the three accused American Indians were guilty of murder. While John Sassamon may indeed have been murdered, the evidence against Tobia, Wampapaquan and Mattashunannamo was insubstantial. However, the court sentenced the three to be hanged. Tobias and Mattashunannamo were executed on June 8, 1675. Wampapaquan was reprieved briefly, but within a month was shot to death.

In retaliation to the executions, open hostilities commenced on June 20 by American Indians who plundered the houses of the English inhabitants in the town of Swansea. The attacks continued over the next several days, and on June 24, as the English were returning from religious worship, they were fired upon by the American Indians, who looted and burned several houses, killed three inhabitants, and wounded two others. Two other colonists who went to find a surgeon to help the wounded were themselves overtaken by the American Indians and slain.

The first help to arrive came from a company of seventeen men from Bridgewater, who were quartered at a fortified house at Gardiner's Neck in Swansea. There they collected seventy people—sixteen men and fifty-four women and children—whom they defended until reinforced. The non-combatants were later transported to Rhode Island for safety.

Massachusetts was quick to respond to Plymouth's appeal for help. Plymouth Colony troops had been ordered to rendezvous at Taunton in preparation to uniting with those from Boston, where they were severely harassed by the American Indians. Lieut. John Freeman, in a letter dated at Taunton, said, "This morning three of our men are slain close by one of our courts of guard, houses are burned in our sight, our men are picked off at every bush. The design of the enemy is not to face the army, but to fall on us as they have advantage."

The Cocheco Massacre occurred when

Penacook Indians attacked the garrisons

in New Hampshire.

The forces that converged on Swansea consisted of a company of infantry under Capt. Daniel Henchman, and a company of one hundred and ten volunteers under Capt. Samuel Moseley, and a company of mounted men under Capt. Thomas Prentice. These three companies, as well as a company from Plymouth Colony under Capt. James Cudworth, of Scituate, were placed under the command of the ranking officer, Capt. Cudworth.

The Bay Colony had also sent emissaries to try to reconcile Philip and Plymouth, but when the colonial troops arrived in Swansea and discovered the mangled bodies of the first colonists killed in the war, authorities were convinced that mediation could not be successful.

The Englishmen had hoped to keep the war confined to Philip's home area of Mount Hope. However, Philip quickly moved beyond the Mount Hope area, and the war could no longer be contained. Within a short period of time, Philip and his men attacked Rehoboth and Taunton and then moved on to Dartmouth and Middleborough. Using a hit-and-run tactic, the American Indians could quickly fall on a town and either destroy it, or loot and burn the outlying houses and steal the livestock.

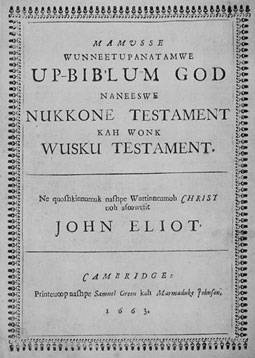

DID YOU KNOW?

John Eliot took upon himself the immense

task of translating the Bible into Algonquian.

In 1663 this translation became the first

Bible printed in America.

Read a biography of John Eliot.

As the colonials became more organized, Philip and his warriors escaped and fled to the temporary safety of Weetamoo's territory.

By July, the Mohegans offered to fight on the English side. Philip, in turn, escaped another English trap and fled for Nipmuck territory where he was able to persuade the Nipmucks to enter the war. In August, fighting spread to endanger Massachusetts towns on two sides, both the ring of towns west of Boston and those settlements on both sides of the Connecticut River. After a raid at Northfield, a relief force under Captain Beers was ambushed south of town and more than half were killed. Three survivors were captured and burned at the stake.

From August 2-4, the Nipmucks besieged the town of Brookfield. On August 22, a group of unidentified Indians killed seven colonists at Lancaster. In retaliation, Capt. Moseley arrested fifteen Hassanamesit (Grafton) Indians near Marlborough for the Lancaster assault and marched them to Boston. In early September, Moseley and his troops attacked the American Indian town of Pennacook.

Meanwhile, the Council of War deliberated over the fate of the American Indian men, women, and children, who had fallen into custody. They concluded that most of the American Indians would be sold as slaves. American Indians south of Plymouth were ordered to come no closer to the colony than Sandwich, under penalty of death or imprisonment. Throughout the colonies, all American Indians, even the friendly Praying Indians, were regarded with suspicion, and they were ordered confined to their Praying Towns.

In September 1675, Deerfield and Hadley were attacked, forcing the colonists to leave their homes and move into forts. Facing a winter with limited food, Capt. Thomas Lothrop led 80 soldiers to gather crops near Hadley. As they returned, the expedition was ambushed by 700 Pocumtucks at Bloody Brook, south of Deerfield. An English force with 60 Mohegan fighters found only seven survivors at the site.

Leaving the northern settlements on the Connecticut River, Philip's warriors moved south, attacking Hatfield, Westfield, and Northampton. The Pocumtucks attacked and destroyed Springfield. The English and Mohegan fighters in western Massachusetts were on the defensive, and by late fall, they were confined to a handful of forts.

By the beginning of November, the Massachusetts Council ordered all of the Praying Indians removed to Deer Island. Despite these precautions, the Nipmucks capture dozens of Christian Indians at Magunkaquog, Chabanakongkomun, and Hassanamesit (Grafton), including James Printer, a Christianized Nipmuck Indian.

Explore the history of the town of

Natick, founded by John Eliot.

Up to this point, the Narragansetts of Rhode Island had remained neutral, but the colonists were suspicious of their intentions. Roger Williams, in the role of peacemaker, had been laboring with the American Indians to avert further bloodshed. During the summer, an American Indian trading post called Smith's Castle (Cocumscussoc) near Warwick, RI, had served as a base for Williams' diplomatic labors with the Narragansetts in an all-out effort to keep them from joining King Philip. Information was received in November that the Narragansetts were harboring some women and children who were aligned with Philip. For harboring Wampanoag refugees, the Commissioners of the United Colonies accused the Narragansetts of being in collusion with the enemy tribes, and ordered the raising of an army to proceed against them. Despite his age (he was now seventy-two), Roger Williams accepted a military commission with the title of Captain and became active in the defense of his Rhode Island home and his fellow citizens.

Plymouth's governor, Josiah Winslow, son of Mayflower passenger Edward Winslow, was named commander-in-chief of the United Colony forces. Richard Smith's trading post, Smith's Castle, was chosen as military headquarters and advance base for the expedition. On December 10, the Massachusetts and Plymouth forces were met at Rehoboth by Richard Smith with several vessels to conduct an advance party to Smith's Castle. The main body followed on foot, arriving three days later with several prisoners taken on the way. One prisoner agreed to guide the English forces to the Narragansetts' main fortress about 12 miles to the southwest, near present-day South Kingstown, RI.

Guided by the American Indian prisoner, General Winslow moved the army near the American Indians' winter stronghold on an "island" in the middle of Great Swamp. A palisaded village of crowded huts, five or six acres in extent, it housed probably as many as a thousand natives of all ages, besides large stores of corn and other provisions.

The bitterly cold weather, though causing much suffering among the troops on the march, proved to be a decisive advantage to the attacking forces. The swamp was so solidly frozen that they were able to move against the fortress normally rendered inaccessible by the surrounding marsh. In the ensuing fight, which raged through a freezing blizzard, the colonial forces stormed the stockade, set fire to the wigwams and turned the village into a funeral pyre. Non-combatant women and children died along with defending warriors. However, Winslow's losses were heavy, too, and he could not sustain the momentum. Many colonials died that night on the return march to Smith's Castle through heavy snow.

The Great Swamp assault promptly increased support for Philip. The Abenaki people to the north joined the war, as did the surviving Narragansett warriors. Their devastating attacks on the outer ring of the Boston area began in February. Groton came under fire, as did Medfield, Marlboro, and Sudbury. While Nipmucks inflicted these damages, Wampanoags and Narragansetts made their way back into Plymouth Colony and Rhode Island to attack Rehoboth and Providence. In the west, Longmeadow, Northampton, and Hatfield were attacked.

Weetamoo and her new husband, the Narragansett sachem, Quanopin, together with the Nipmuck Indians, successfully raided the town of Lancaster and succeeded in storming the garrison where settlers had taken refuge. Among those inside was Mary Rowlandson, a Puritan minister's wife, who was taken captive and spent the next six weeks of the winter being taken back and forth across Massachusetts, barely clinging to life. After three months she was ransomed, an indication of the declining power of the American Indians, who were now without food, short on muskets and powder, and facing large numbers of colonists.

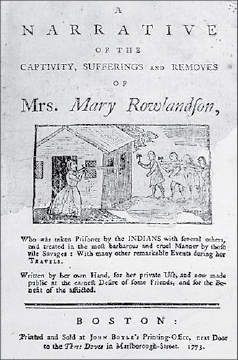

Mary Rowlandson published an account

of her time with her Indian captors. Here

you can read her captivity narrative,

Narrative of the Captivity and the

Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson.

In March 1676, Roger Williams lost the home where he had lived for some years when a large force of American Indians descended on Providence and burned about fifty houses. In the same month, Plymouth Colony suffered a serious blow. Near Providence, on the Pawtucket River, Capt. Michael Pierce leading a company consisting of colonists and some American Indians, was defeated by a large group of Narragansett. Despite the fact that the colonists fought fiercely, the militia was decimated.

The first part of the war favored Philip and his allies, whose daring raids had proved too much for the colonists. While the colonists were regularly drilled in their town militias, they were not trained or familiar with the fighting methods and strategies used by the American Indians. In addition, colonial troops did not have adequate provisions because food was in short supply. Crops were lost in towns that were burned and in towns that were not attacked the crops could not be harvested because men were away fighting.

After their initial defeats, however, the colonists began to learn how to fight in the same way that the American Indians did. Philip and his allies had little chance in the long run against the combined resources of the United Colonies with their population of seventy thousand and reserves of food and ammunition. Winter fighting had robbed Philip's people of their reserves of food, ammunition, and shelter. Women and children were especially vulnerable once their crops and homes had been destroyed at the onset of winter. Since they were never unified, the various tribes were never able to subordinate their individual interests to a total war effort. As the war progressed, many of the American Indians who were aligned with the colonists were of great help, and they made up substantial parts of the colony's forces.

Read more about Roger Williams. He was

the founder of Rhode Island and played

a role in King Philip’s War. Although

there are images that purport to depict

Roger Williams, the New England Historical

Society states that there are no known

authentic images of Williams.

By May of 1676, the colonists were able to repel an attack on Hadley. Going on the offensive, they attacked sleeping American Indians near Deerfield. Mary Rowlandson was also released and returned to Boston that month, as her captors were quickly running out of provisions for themselves and unable to support prisoners.

In June, Massachusetts issued a declaration of amnesty for American Indians who were willing to surrender. Parties of half-starved American Indians surrendered all over New England. Nearly two hundred Nipmucks surrendered in Boston alone. Major John Talcott and his troops began moving through Connecticut and Rhode Island, capturing Algonquians who were moved out of the colonies and enslaved.

An important figure in the war for Plymouth was Capt. Benjamin Church, son of Richard Church and Elizabeth, who was the daughter of Mayflower passenger Richard Warren. Church had distinguished himself early on in fighting at Swansea, in the Great Swamp Fight, and in guerrilla-type operations throughout Plymouth Colony. Church had been on friendly terms with American Indians before the war, and during the war he was sometimes able to get them to change sides almost instantly.

Around the beginning of August, Church just narrowly missed capturing Philip on the Taunton River, but was able to capture his wife and son. After a quick return to Plymouth, Church headed out again to find Philip. The war had completed a full circle, and Philip, now destitute and with but a few tired, hungry men, had come back to where it all started, his one-time home at Mount Hope. Church was across the water at Aquidneck Island when a deserter from Philip's camp told him where the Wampanoag chief was hiding. Before leading a charge on Philip's camp, Church posted pairs of men in a circle surrounding the camp. When his main force charged, Church knew Philip would have nowhere to flee except into the ambush. A waiting pair of men, a colonist and an American Indian, saw someone running toward them. The colonist aimed his gun first, but his gun misfired. The American Indian killed the runner. It was Philip. A victorious Church announced that since Philip "had caused many an Englishman's body to be unburied and to rot about ground, not one of his bone should be buried." He ordered Philip's head severed and his body quartered. Philip's head was taken to Plymouth where it was displayed for months.

Steadily, the various tribal groups were captured, killed, or sold into slavery in the West Indies, as indeed were Philip's own family. On August 28, 1676, Philip's captain, Anawan, was captured by Church at a place known today as Anawan's Rock, in the east part of Rehoboth.

Quinapin, Weetamoo's Narragansett husband who had been second in command in the Great Swamp Fight, was captured in 1676, taken to Newport, RI, and shot. Weetamoo and her followers fled to the Niantic country (Westerly, RI). Still pursued, she headed for Swansea, where she was betrayed by someone who deserted her camp. A force from Taunton captured her followers. Weetamoo attempted to escape on a hastily-built raft. She drowned and her corpse was eventually found on the beach of Gardiner's Neck, in Swansea. Her head was cut off and taken to Taunton.

Although some sporadic fighting continued in Maine, by the summer of 1676 the war was over. The American Indians of southern New England had been reduced to a few small groups cooped up in special villages, their way of life and environment destroyed forever. Among the casualties were Eliot's Praying Towns, most of whose inhabitants, though friendly, had been interned on Deer Island near Boston in conditions of great hardship. Afterwards only four towns remained, with the prospects for racial harmony even among the converted hopelessly compromised.

The net result for the colonists was the clearing of the coastal areas for settlement. The war had been fought, however, at a terrible price. Twelve towns had been destroyed, half the rest had suffered some damage, almost one out of every fifteen men of military age had been killed, and all of the United Colonies had incurred large debts. The scars of the war were to remain for a long time.

King Philip's War | Bibliography

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Metacom, King Philip, or Philip of Pokanoket." Accessed 6/17/19. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/377406/Metacom

- Greatsite Marketing. "English Bible History: John Eliot." Accessed 6/17/19. http://www.greatsite.com/timeline-english-bible-history/john-eliot.html

- History of the USA. Converted from Henry William Elson's History of the United States of America. The MacMillan Company, NY, 1904. "Colonization—New England." Accessed 6/17/19. http://www.usahistory.info/New-England/

- Hougton Mifflin. "Mary White Rowlandson." Accessed 6/17/19. http://college.cengage.com/english/lauter/heath/4e/students/author_pages/

colonial/rowlandson_ma.html - Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities. "Mass Moments: King Philip's War Breaks Out." Accessed 6/17/19. http://massmoments.org/moment.cfm?mid=184

- Military History Online. "Philip's War: America's Most Devastating Conflict." Accessed 6/17/19. http://www.militaryhistoryonline.com/horsemusket/

kingphilip/default.aspx - National Park Service. "Historic Great Swamp Opened at Last." Accessed 6/17/19. https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/regional_review/vol1-6f.htm

- New England Historical Society. “The Mysterious 1644 Portrait of Roger Williams.” Accessed 6/17/19. http://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/portrait-of-roger-williams/

- The Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Connecticut. "1675—King Philip's War." Accessed 6/17/19. http://www.colonialwarsct.org/1675.htm

- Stratton, Eugene Aubrey. Plymouth Colony: Its History and People 1620-1691. Ancestry Publishing. Salt Lake City, Utah. 1986.

- Sultzman, Lee. "Wampanoag History." Accessed 6/17/19. http://www.tolatsga.org/wampa.html

- United States Genealogical Network. "Soldiers in King Philip's War." Accessed 6/17/19. http://www.usgennet.org/usa/topic/newengland/philip/1-10/intro6.html

- Native New England. "Mary Rowlandson—Captive in 1675/76." Accessed 6/17/19. https://nativenewengland.wordpress.com/2016/04/04/mary-rowlandson-captive-in-167576/

King Philip's War | Image Credits

- Philip, King of Mount Hope; Fanciful Portrait of King Philip | Artist: Paul Revere, 1772; from The Beginnings of New England by John Fiske, 1930; American Centuries

- Josiah Winslow | Artist: Unknown, 1651; Pilgrim Hall Museum

- A Garrison House | Photographer: Unknown, 19th century; Dover Public Library

- Eliot Indian Bible | Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God, title page. Cambridge, MA: printed by Samuel Green and Marmaduke Johnson, 1663; Special Collections, University of Pennsylvania Library

- Mary Rowlandson Book Cover | Narrative of the Captivity and the Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, title page. Cambridge, MA: printed by Samuel Green, 1682; Washington State University

© 2020 Small Planet Communications, Inc. + Terms/Conditions + 15 Union Street, Lawrence, MA 01840 + (978) 794-2201 + planet@smplanet.com