Small Planet Communications, Inc. + 15 Union Street, Lawrence, MA 01840 + (978) 794-2201 + Contact

The area on the eastern seaboard of America that became the English colony and then the state of New Jersey encompasses a landscape of mountain ridges, fertile valleys and fields, pine forests, salt marshes, and long white beaches stretching from the mouth of the Hudson River and the Atlantic to the Delaware River and Bay. This land attracted European colonists.

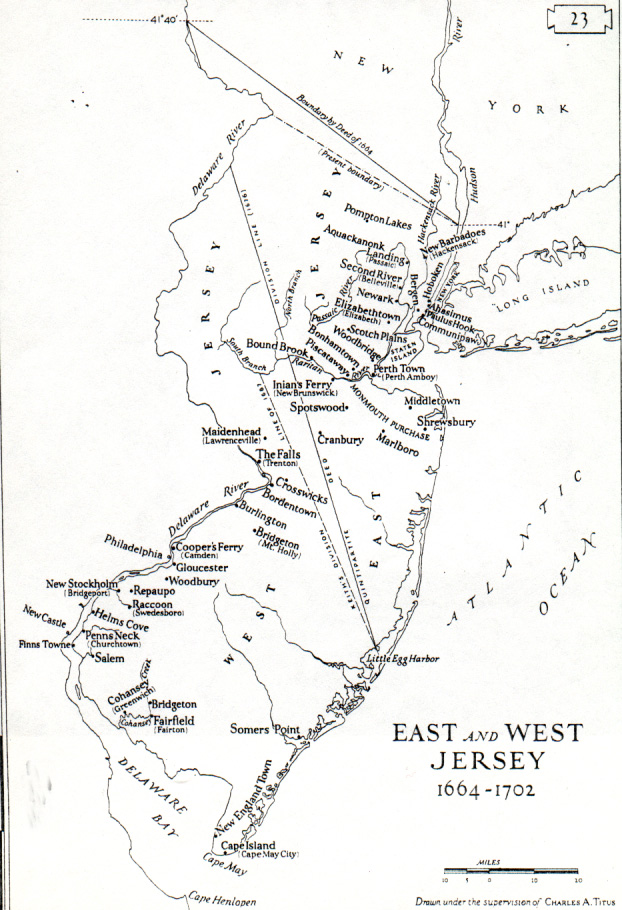

Click the image to view an enlarged map of

East and West Jersey.

Explore historical maps of New Jersey and a

timeline of New Jersey history.

The earliest inhabitants of the Northeast, including New Jersey, are believed to have settled the area between 12,000 and 15,000 years ago—at the end of the most recent Ice Age. By the time European colonists began arriving, the inhabitants of the area were the Lenni Lenape, or Delaware, Indians. It is not known exactly how many Delaware lived in the region when European colonists started arriving. Estimates range from between 6,000 and 20,000 people.The Delaware spoke Algonquian languages and were primarily farmers. They supplemented their crops of corn, squash, and beans with fish, wild game, berries, nuts, herbs, and roots. They used ashes from their fires, fish bones, and shells as fertilizer in their gardens.

The arrival of European colonists began the decline of these native inhabitants. Many died of diseases introduced by the settlers. The remainder were forced from their homes by the Europeans' desire for land. As the areas where they could live and hunt shrank, different groups of Delaware migrated, eventually settling in several sites ranging from southern Ontario, Canada, to Oklahoma. Although an attempt was made in 1758 to provide the remnants of the Delaware with a reservation at Brotherton (now Indian Mills), New Jersey, most of the remaining Delaware left New Jersey around 1800.

Learn more about

Fort Elfsborg.

The New Jersey area claimed by the English, French, and Dutch was on the basis of explorations from 1524 to 1623 by John Cabot, Henry Hudson, Giovanni da Verrazano, and Cornelius Mey. Some of the first Europeans to set foot in New Jersey were sailors from the Dutch-owned ship Half Moon, commanded by English explorer Henry Hudson, in 1609. The Dutch established New Netherland in what is now New York and New Jersey. Dutch adventurers, fur trappers, and traders followed. People from Sweden established small settlements on the Delaware River in southern New Jersey, beginning with Fort Elfsborg in 1638. It was there that Swedish and Finnish settlers built likely the first log cabins in North America.

Cultural differences in trade and land ownership practices created conflict, and the earliest Dutch settlements in New Jersey were destroyed during conflicts with American Indians. In 1655 the colonial governor, Peter Stuyvesant, expelled the Swedish. In 1660, under Stuyvesant's direction, the fortified village of Bergen—present-day Jersey City—became the first permanent New Jersey settlement. Other Dutch settlers established Fort Nassau on the Delaware River in 1623 and Jersey City at the mouth of the Hudson River in the early 1630s.

In 1664, England began to press its colonial claims. The English had never recognized Dutch or Swedish claims to New Jersey, basing its right to the area on Cabot's voyage and on the power of its navy. In 1664 the Dutch surrendered New Netherland to the English, who renamed the area west of the Hudson River New Jersey, for the island of Jersey in the English Channel.

Read a brief article about

Sir George Carteret, one of

the proprietors of New Jersey.

King Charles II of England granted all of the captured Dutch colony to his brother, James, Duke of York. The name "New Jersey" was first used in a deed in which James granted proprietorship over the area to Lord John Berkeley and Sir George Carteret. Unaware of this transaction, the royal governor of New York parceled out tracts of land in Monmouth County and at Elizabethtown (now Elizabeth) to Puritans from New England and Long Island. Philip Carteret, a brother of one of the new proprietors, received a commission as Governor of New Jersey, and landed at Elizabeth in August 1665.

Almost immediately, conflict arose between the proprietors and the Puritans over land claims and the right to establish a government. Political and religious differences intensified the friction; the proprietors were Anglicans and loyal to the king, while the Puritans were dissenting Protestants. Sporadic riots broke out over the demands of the proprietors that landholders pay them rent. However, the colony continued to grow. Except for a brief return to Dutch rule in 1674, New Jersey remained British until the American Revolution.

The two proprietors, Berkeley and Cateret, were also involved in the Carolinas and did little to advance their new possessions. In 1674, Berkeley sold his share of the colony to two Quakers, Edward Byllinge and John Fenwick. When a dispute over the terms arose, William Penn was called in as arbitrator. He gave one-tenth of the province and a considerable sum of money to Fenwick and gave the remainder of the territory to Byllinge. When Byllinge went bankrupt in 1676, his creditors, which included Penn, took control of his share under a deed which divided the colony in half — West New Jersey (Berkeley's portion, now owned by Penn and his fellow Quakers) and East New Jersey (Carteret's portion). Carteret retained control of the eastern half until 1682 when Penn and 11 other prominent Quakers jointly purchased East New Jersey. In that very transaction lay another problem: With so many proprietors, confusion was inevitable. There were long-lasting boundary disputes and enduring political, economic, and social differences between the two Jerseys.

Settlements were sparse and scattered, yet New Jersey's highways were the best in the colonies due to the area's location between New York and Philadelphia, and between the northern and southern colonies. West New Jersey served as a haven for persecuted English, Irish, Welsh, and Scottish Quakers. The company shareholders became the board of proprietors, who acted as landlords and the government of the colony. They allowed settlers to spread across the countryside in farms of more than 600 acres. East New Jersey, largely owned by the Scottish partners of Carteret's heirs, set up huge estates, imported several hundred indentured servants, and refused to sell land to independent farmers. Many New Englanders were attracted to the area. The Dutch brought the first African slaves into Bergen County in East Jersey. All of these people, along with Swedes, Scots, Irish, Germans, and French Huguenots, gave New Jersey greater cultural diversity than any other area, although this diversity contributed to New Jersey's persistent lack of cohesiveness and identity.

Under the original two proprietors, the charter for the government of New Jersey was the Concessions and Agreements of the Lords Proprietors, which provided for religious freedom, trial by jury, and a representative assembly. In 1677 Penn wrote a second charter for West Jersey called the Concessions and Agreements, which guaranteed freedom of religion and personal liberty, and provided for the annual election by secret ballot of a representative assembly with limited powers of taxation. By the time the two New Jersey proprietorships were united as a royal colony, a tradition of self-government had been established.

Learn about royal

governor William Franklin.

Learn about important women in

New Jersey history.

Read about Penelope Van Princis

Stout, an early settler who was

shipwrecked off the coast of New

Jersey, then attacked by American

Indians. Penelope managed to

survive her horrible wounds until she

was rescued by other American

Indians who nursed her back to health.

New Jersey's Raritan Bayshore was

infested with pirates in the late 17th

and early 18th centuries. Learn more

about one of the most famous pirates

who visited, Captain Kidd.

In 1702 the boards of proprietors in both sections of New Jersey turned their governing authority over to Queen Anne, who united the two into a single royal colony. Queen Anne appointed Lord Cornbury to be Governor of New York and New Jersey, but each region continued to have a separate assembly. In 1738 New Jersey petitioned for a distinct administration, and Lewis Morris was appointed governor. The population was then about 40,000. The last royal governor was William Franklin, the natural son of Benjamin Franklin. However, the two proprietary organizations continued to act as landlords, holding title to all unclaimed land in New Jersey.

Under the royal government, local self-rule was curtailed and the colony was bound more closely to England. Despite political unification, each section insisted on maintaining its own capital. The assembly, which shared colonial rule with the royal governor, was forced to hold its sessions in each capital in alternating years. Differences between the two sections remained, but they united to present a common front against the royal governor. In trying to restore harmony and obedience to royal authority, the governors were forced until 1738 to divide their attention between New Jersey and New York, and many of the crown's representatives were incompetent. This enabled the colonists to exercise a greater amount of self-government than the monarchy desired. Especially important was the assembly's power to collect taxes for the governor's salary. Governors who remained responsible to the king and opposed the interests of the colonists often went unpaid.

New Jersey | Bibliography

- Cumberland County New Jersey. "History of Agriculture in Cumberland County." Accessed 6/19/19. http://www.co.cumberland.nj.us/history-of-agriculture

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "New Jersey." Accessed 6/19/19. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/411672/New-Jersey

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "The Land: Traditional regions of the United States." Accessed 6/19/19. https://www.britannica.com/place/United-States/Traditional-regions-of-the-United-States

- Library of Congress. "William Penn and His Holy Experiment." Accessed 6/19/19. https://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/october-14/

- National Park Service. "Archeology Program: The Earliest Americans." Accessed 6/19/19. http://www.nps.gov/history/archeology/eam/landmarks.htm

- New Jersey City University. "Jersey City: Past and Present." Accessed 6/19/19. http://www.njcu.edu/programs/jchistory/About.htm

- New Netherland Institute. "A Tour of New Netherland: Fort Elfsborg." Accessed 6/19/19. http://www.newnetherlandinstitute.org/history-and-heritage/digital-exhibitions/a-tour-of-new-netherland/delaware/fort-elfsborg/

- The Swedish Colonial Society. "A Brief History of New Sweden in America." Accessed 6/19/19. http://www.colonialswedes.org/History/History.html

- The Twickenham Museum. "Lord John Berkeley." Accessed 6/19/19. http://www.twickenham-museum.org.uk/detail.asp?q=Berkeley&imageField.x=0&imageField.y=0&ContentID=86

- U-S-History.com. "Settlement of New Jersey." Accessed 6/19/19.

http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h591.html

New Jersey | Image Credits

- East and West Jersey, 1664–1702 | Adams, James T., Ed. Atlas of American History. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1943. (p. 23)

- Sir George Carteret | Artist: Unknown; The Diary of Samuel Pepys

- William Franklin | Artist: Mather Brown, 1790; Franklin and Marshall College

- Captain Kidd | New England Historical Society

© 2020 Small Planet Communications, Inc. + Terms/Conditions + 15 Union Street, Lawrence, MA 01840 + (978) 794-2201 + planet@smplanet.com