Small Planet Communications, Inc. + 300 Brickstone Square, Andover, MA 01810 + (978) 794-2201 + Contact

During colonial times, many people moved to the colonies because of religious intolerance and persecution. In England, Henry VIII had broken away from the pope and Roman Catholic Church in the 1530s. For much of the 1500s and 1600s, and even into the 1800s, English Catholics faced persecution and worshipped underground.

George Calvert and his sons, Cecilius (Cecil) and Leonard, decided to establish the colony of Maryland in the New World as a haven for Catholic refugees. They also hoped to gain wealth from its development. Maryland's 1632 charter made the Calverts feudal lords and proprietors, with possession and control of the colony's wealth, profits, land, and much of its governance.

While Maryland indeed became a safe place for persecuted Catholics to settle, many Protestants and Puritans left other colonies to settle there, as well. Maryland became torn by religious friction and political struggles between Catholics and Protestants. By 1649, Maryland had passed a law promising religious tolerance—a landmark in colonial American history. Although religious struggles would continue in colonial Maryland, it was generally considered more tolerant than other colonies.

The first people to settle in what is now Maryland arrived more than 10,000 years ago. These American Indian groups lived a nomadic lifestyle, hunting and gathering. Around 1,500 years ago, they began growing squash, beans, and tobacco. In time, American Indians in this area began staying in villages for most of the year or even year-round. Most of these American Indians were Woodland Indians who spoke an Algonquian language. Some of the key American Indian tribes of Maryland at the time of European settlement included the Piscataway, Yaocomaco (or Yeocomico), Shawneee, Accohannock, Nanticoke, and Susquehannock. European settlement dramatically changed this area for its American Indian population. For example, in 1500, before European contact, the population of American Indians in the Chesapeake Bay area was thought to have been around 24,000 people. By 1650, due to war, disease, and migration, less than 3,000 American Indians remained in the Bay area.

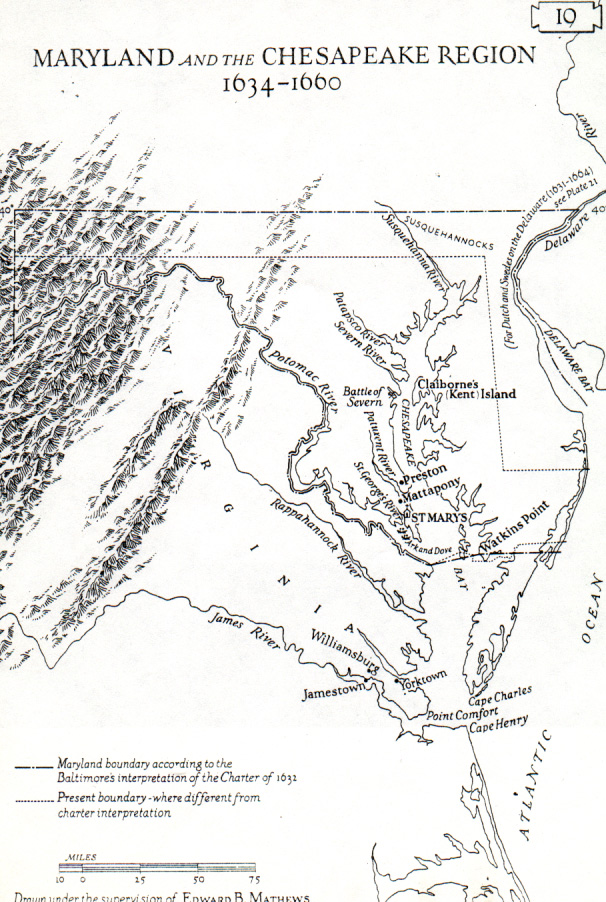

The Chesapeake Bay area is thought to have been first explored by Europeans in the early 1500s. English Captain John Smith later explored and mapped this region in the early 1600s. However, the colony of Maryland was not chartered until 1632 or formally settled until 1634. It was originally intended by its proprietors, George Calvert—the first Lord Baltimore—and his son Cecilius (Cecil)—the second Lord Baltimore—to be a refuge for English Catholics and a source of family prosperity.

George Calvert did not become a Catholic until adulthood. For many years, he was a prominent politician. In 1617, he was knighted and then in 1619 named a secretary of state. When Calvert announced that he had converted to Catholicism in 1625, he had to give up his political position. That same year, Calvert was given the title of Baron (Lord) Baltimore.

George Calvert's interest in the New World began when he was persuaded to invest in the Virginia Company. He also had an interest in the New England companies. Calvert started a small settlement of his own in Newfoundland, chartered under the name Avalon. When he visited his Newfoundland colony in 1627, however, he found the climate too harsh for any hopes of a major success in developing it. In addition, controversy arose over his Roman Catholic practices.

Seeking land with a warmer climate where Catholics could worship freely, George Calvert requested a grant for a tract of land near Virginia along northern Chesapeake Bay (present-day Maryland and Delaware) in 1629. Sailing to Virginia without a charter, the Virginians refused to allow him to settle there because of his Catholicism. They also sought to prevent him from obtaining a charter in any Virginian territory. Calvert returned to England and with his son Cecil persevered in obtaining the necessary charter. George Calvert's death prevented him from seeing the charter that was issued on June 20, 1632. The charter granted him and his heirs territory in the upper Chesapeake, to be called Maryland in honor of the queen.

Calvert's charter, a proprietary charter, was strongly feudal in tone. Calvert and his heirs were to be absolute Lords and Proprietors. As the proprietors of the colony, they could grant titles and lands with manorial rights. In addition they could incorporate towns, license trade, create courts of law, coin money, and even raise an army. Regarding taxation and legislation, however, the proprietors could only collect taxes and enact laws subject to the consent of the freemen of the colony. This latter aspect of Maryland's charter is another example of democracy gaining an early toehold in colonial America.

Calvert's heir, the second Lord Baltimore, Cecil Calvert, organized the expedition to found the colony. To ensure political support for the charter in England, Cecil remained behind, naming his brother, Leonard, to lead the expedition and serve as the colony's first governor. In keeping with his father's wishes to promote religious toleration and help ensure the colony's financial success, Cecil invited both Catholics and Protestants to settle Maryland. Most of the settlers—about 140 in number—were Protestants (as best as can be gleaned from the historical records). Many were indentured servants. The settlers also included about 20 gentlemen, some of their wives, and two Catholic priests.

On November 22, 1633, the settlers, aboard Cecil's two ships, the Ark and the Dove, left Cowes on the Isle of Wight, England, for the Maryland colony. They took a southern route, surviving stormy weather and even being separated from each other. Then they stopped for supplies in the West Indies before reaching Chesapeake Bay in early March 1634. On March 25, 1634, the settlers rowed ashore to a small island, which they named St. Clement's, located in the mouth of the Potomac River (part of the Chesapeake Bay water basin). They gave thanks and held what is considered to be the first Catholic Mass in the English colonies. Their thanksgiving is now celebrated as Maryland Day, a state holiday.

After negotiating for land with two local American Indian tribes, the Piscataway and Yaocomaco, Leonard Calvert moved the settlers to a better site for a permanent settlement. This new site was located farther downstream from St. Clement's Island, along the banks of a tributary of the Potomac, now called St. Mary's River. Here, they founded their settlement, which they named Saint Maries, or St. Mary's City—the Maryland colony's first capital. A fort was built with several cannons mounted on top. Since the Yaocomaco people had already cleared some land, a crop of corn could be grown for food. Tobacco would be grown for trade and export. Maryland's first settlers avoided the mistakes of Virginia's first settlers, focusing on farming and trading instead of seeking gold. They also learned new farming techniques from the local American Indians.

DID YOU KNOW?

Calvert left the title of the grant

blank on the charter when he

gave it to the king to sign. The

king filled in the blank with

"Terra Maria", which translates

to Maryland. Click to learn more

about Queen Henrietta Maria,

namesake of Maryland.

Lord Baltimore offered generous terms for land in the new colony. The original (male) settlers who paid their own way—and that of five other men—were promised a grant of 2,000 acres (those after 1635 would receive 1,000 acres). For those men who brought over fewer than five men, they would receive 100 acres plus another 100 for each man. A married man received 100 acres for himself, another 100 for his wife, and 50 for each child under 16. These land-owning settlers also paid a modest rent (called a quit rent) to the proprietor, Lord Baltimore.

One of the many notable first settlers of Maryland was Mathias de Sousa, who came over on the Ark as an indentured servant to Father Andrew White, a Catholic priest. De Sousa likely was of African and Portuguese descent. He's considered the first free African-American to live in Maryland, earning his freedom in 1638. De Sousa then became a fur trader and sailor. In the early 1640s, de Sousa was elected to and voted as a member of the Maryland Assembly.

Around the time de Sousa was voting in the assembly, Maryland was bringing over enslaved Africans to work its tobacco fields. Tobacco had become the main cash crop of early colonial Virginia and Maryland. It was even used in place of money at times. However, growing tobacco required more labor than could be supplied by indentured servants. As a result, increasing numbers of enslaved Africans were brought over to work Maryland's tobacco plantations. Slavery and tobacco would continue to play leading roles in colonial Maryland's history and culture.

Although England had overruled attempts by Virginia to prevent the Maryland colony from being established, Lord Baltimore soon encountered more trouble with the Virginians as Maryland became settled. Back in 1631, William Claiborne of Virginia had created an independent trading station on Kent Island in Chesapeake Bay. Claiborne refused to recognize Lord Baltimore's jurisdiction over Kent Island. As a result, armed conflict broke out in 1635 between Baltimore's and Claiborne's forces. Although Claiborne kept up the struggle to retain Kent Island for many years—right up to his death—it eventually became part of Maryland.

Read a biography of Leonard

Calvert, first Governor of Maryland.

When civil war erupted in England in the 1640s between Catholics and Protestants, a violent period in Maryland's history also resulted. In 1645, Richard Ingle, a Protestant sea captain, led a rebellion against Governor Leonard Calvert to protect Maryland's Protestants. Claiborne seized Kent Island, while Ingle captured St. Mary's, forcing Governor Calvert to seek refuge in Virginia. This armed conflict became known as Ingle's Rebellion and lasted about two years. Governor Calvert returned and restored order, as Ingle had already fled. However, Governor Calvert died soon after, in 1647.

When Governor Leonard Calvert died, Maryland was still in turmoil. From his deathbed, Governor Calvert had appointed Margaret Brent as the executor of his estate. At the time, this appointment of a woman executor was unusual. But Margaret Brent was an exceptional woman of these times. Brent was from a family of English Catholic gentry, who remained unmarried in a land where men greatly outnumbered women. As an unmarried woman in Maryland, Brent owned and ran her property as she deemed. Margaret's decisive actions in resolving Leonard's affairs, especially in paying off Calvert's soldiers who were near mutiny, helped ensure that the settlement would survive these trying times.

As if these deeds weren't notable enough, Brent is perhaps best known for her appearance before the Maryland Assembly. On January 21, 1648, Brent asked the assembly to grant her two votes: one for herself as a landowner and one as executor of Governor Calvert's estate. Although her request was denied, Brent is often considered the first suffragette of America.

To further calm religious turmoil in Maryland at this time, Lord Baltimore (Cecil Calvert) appointed a Protestant, William Stone, as governor. Stone took office in 1649, becoming Maryland's first Protestant governor. That same year, England's King Charles I was beheaded, and Lord Baltimore sent the Maryland Assembly a bill for religious toleration known as the "Maryland Act Concerning Religion," often called the "Act of Toleration," but perhaps best known as "The Toleration Act." Lord Baltimore hoped to have enacted into Maryland law the religious toleration that the colony had practiced since its beginning. With Maryland's Assembly divided about equally between Protestants and Catholics, members rewrote some of the bill to put their stamp on it. The assembly then passed the Toleration Act into law on April 21, 1649.

DID YOU KNOW?

Margaret Brent is sometimes

thought of as the first woman

lawyer in America. She was

involved in over 100 court cases

—and won them all.

The Toleration Act is considered an important milestone in colonial American history. It was an early attempt to ensure that the state and church were kept separate. Although the Act would be repealed in the late 1600s, it influenced the United States Constitution and Bill of Rights—as the First Amendment to the Constitution ensures the separation of church and state.

For the next 50 years or so, religion continued to divide colonial Marylanders. At stake was the proprietary system of the Calverts. In 1649 Governor Stone had invited Puritans from Virginia to settle in Maryland. They founded Providence on the Severn River, near present-day Annapolis. For the next several years, the Puritans struggled with Stone for political power. The assembly, now controlled by Puritans, passed anti-Catholic legislation, as well as other laws restricting religious freedom. In March 1655, Stone and a force of about 100 soldiers made an unsuccessful attempt to recapture the government in the Battle of the Severn. Maryland would remain under the control of the Puritans for several more years. Ultimately, this religious and political struggle was resolved in London, but just for a time. Oliver Cromwell, who now ruled England, had little sympathy for the extreme actions of the Maryland Puritans. In 1657 Lord Baltimore was reinstated as proprietor.

Until England's Glorious Revolution of 1688, which brought the Protestants William and Mary to the throne, proprietary authority remained mostly unchallenged in Maryland. The colony continued to grow, as did the number of enslaved Africans brought to work its plantations. As the number of indentured servants willing to come over to Maryland decreased, Maryland's economy grew dependent on slave labor. In 1664, the assembly enacted laws officially allowing slavery and making it a lifelong condition (unlike an indentured servant who earned his or her freedom after a certain number of years).

Read about Cecil Calvert,

Second Lord Baltimore.

After the Glorious Revolution, the resentment Maryland's Protestants held toward the province's Catholic leaders in St. Mary's City boiled over in the Maryland Revolution of 1689. In that year, John Coode, a sheriff from Charles County, and a group of Protestant rebels overthrew the proprietary government of the Calverts. William and Mary then placed Maryland under royal control, which lasted until 1715. The Church of England was made the official church of Maryland, replacing the 1649 Toleration Act. In 1694–1695, the colony's capital was moved from Catholic-dominated St. Mary's City to Protestant-dominated Anne Arundel Town—and renamed Annapolis after Princess Anne, Queen Mary's daughter.

Although Maryland was returned to its proprietary status—the fourth Lord Baltimore, Benedict Calvert, was a Protestant—the assembly disenfranchised Maryland's Catholics in 1718. It wasn't until 1776 that Maryland's Catholics were re-enfranchised. In general, Maryland remained a center of American Catholicism, largely through the efforts of John Carroll. Carroll was born in Maryland in 1735 and was a cousin of Charles Carroll, one of Maryland's signers of the Declaration of Independence. In 1789, Carroll was named the first bishop in the United States, and he was also a founder of Georgetown University.

Maryland continued to grow during the 1700s. By then, most of the American Indians in the colony had been pushed out, killed in various conflicts, or died from diseases, such as smallpox. Some estimates suggest that less than 150 of the Piscataway population survived in Maryland by 1700. At about this time, it's also thought that only two tribes remained on Maryland's Eastern Shore, one being the Nanticoke.

Learn more about the day

the Mason-Dixon line was

formed by clicking here.

In 1729, Baltimore Town was chartered, becoming a major port and shipbuilding center. Although Baltimore did not officially become a city until 1796, the Continental Congress met there for a brief time in 1776–1777 after escaping the British in Philadelphia. During the Revolutionary War, Baltimore served as a major supply center. Baltimore was also home to a significant population of free African-Americans, even though enslaved Africans continued to be brought into Maryland during the 1700s. In Prince George's County, slaves made up over 50 percent of the county's population by the mid-1700s. Prince George's County, also called the tobacco county, was dependent on tobacco—and enslaved African-Americans for labor. In fact, Virginia and Maryland's economies were so dependent on tobacco, more than half of all slaves lived in these two colonies in the mid- to late 1700s.

One free African-American who lived most of his life on his family farm in Baltimore County was Benjamin Banneker, born in 1731. Banneker became a self-taught scientist and published a very popular series of almanacs, for which he calculated the tides, sunrises, and sunsets, and correctly predicted an eclipse. During the 1790s, Banneker played a leading role in planning Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States.

As Maryland grew, it came into conflict with another growing colony on its northern border, Pennsylvania. The two colonies had been disputing their shared border for many years, almost since the founding of Pennsylvania in the late 1600s. Finally after years of failed negotiations, the matter was settled by an English court, which instructed two British astronomers and surveyors, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, to establish the border. From 1763 to 1767, Mason and Dixon trekked along a mostly wilderness area, surveying and setting stone markers (at set intervals, markers had an "M" or the Calvert coat-of-arms on the south-facing sides and a "P" or the Penn coat-of-arms on their north-facing sides). When they had completed their work, the Maryland-Pennsylvania border (and that of Maryland and Delaware) had finally been established. The Maryland-Pennsylvania border, which stretched for 233 miles, became better known as the Mason-Dixon line. This line divided the North from the South, slave states from free states, during the Civil War.

Maryland also played an important role in the French and Indian War of 1754–1763. Settlers of western Maryland, like other settlers of the early western frontier of Colonial America, came into conflict with the French and American Indians. In Maryland, two forts were built for protection: Fort Cumberland (now the City of Cumberland) and Fort Frederick (near Hancock). During this war, Fort Cumberland served as George Washington's headquarters for a time and as an important British staging and supply point. Fort Frederick also served as a supply center and was a unique frontier fort for its time, built with stone walls instead of the more typical wood and earth.

After the French and Indian War, Marylanders, like the other colonists, began to come into greater conflict with England over its policies. As a way to raise money to pay off England's war debts—and to pay for administering its colonies—the English government passed a series of acts in the 1760s and 1770s, such as the Sugar Act (1764), the Stamp Act (1765), and the Tea Act (1773). One well-known opponent of the Stamp Act was Danial Dulany of Annapolis. Dulany wrote a popular pamphlet at the time, arguing for no taxation by England without colonial representation. Samuel Chase and William Paca, two of Maryland's four signers of the declaration of Independence, also led protests against the Stamp Act.

Although the Boston Tea Party may be the American colonies' most famous protest against the Tea Act, Maryland held two of its own tea parties in 1774. The first was in May in Chestertown, where colonists raided a tea ship during the day without any disguises. The second was in October in Annapolis, where the Peggy Stewart lay with her cargo of imported tea. The ship's owner, Anthony Stewart, had paid the tea tax even though Maryland voted to ban British imports in support of Boston, whose harbor had been closed. When a mob threatened Stewart (and his family), he agreed to burn the tea—and his ship.

Learn more about

Maryland history.

As the American colonies moved closer to independence, Marylanders again played an important role. In addition to Chase and Paca, Charles Carroll and Thomas Stone also represented Maryland at the Continental Congress and were signers of the Declaration of Independence. Paca served three terms as Maryland's governor and as a federal district judge. Chase served as a justice of the United States Supreme Court. Stone died relatively young at age 44, shortly after the death of his beloved wife. Carroll was the only Roman Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence, and he was the last surviving signer upon his death in 1832. For a time in late 1776 and early 1777, the Declaration of Independence was kept in Baltimore for safekeeping.

Maryland | Bibliography

- Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. "Cumberland, Maryland." Accessed 6/6/19. https://www.achp.gov/preserve-america/community/cumberland-maryland

- American Indian Cultural Center. "Piscataway Indians: About Us." Accessed 6/6/19. http://piscatawayindians.org/aboutus.html

- Anne Arundel County, Maryland. "County History." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.aacounty.org/AboutAACo/history.cfm

- Archiving Early America. "Fighting for a Continent: Newspaper Coverage of the English and French Warfor Control of North America, 1754-1760," by David A. Copeland. Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.earlyamerica.com/review/spring97/

newspapers.html - British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). "The Glorious Revolution," by Dr. Edward Vallance. Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/civil_war_revolution/

glorious_revolution_01.shtml - British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). "The Gunpowder Plot," by Bruce Robinson. Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/civil_war_revolution/

gunpowder_robinson_01.shtml - Brompton Books. "The Almanac of American History," ed. by Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. Published by Barnes and Nobles Books, NY, 2004.

- Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels. "The Baltimore Basilica." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.olacathedral.org/cathedral/arch/balt_bas.html

- Catholic Encyclopedia. "Charles Carroll of Carrollton." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03379c.htm

- Catholic Encyclopedia. "Ecclesiastical History." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07365a.htm

- Catholic Encyclopedia. "George Calvert." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03192a.htm

- Catholic Encyclopedia. "John Carroll." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03381b.htm

- Chesapeake Bay Program. "Bay Plain and Piedmont." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.chesapeakebay.net/content/publications/cbp_19653.pdf

- Chesapeake Bay Program. "Indigenous Peoples of the Chesapeake." Accessed 6/6/19. https://www.chesapeakebay.net/discover/history/archaeology_and_native_americans

- Chestertown Tea Party Festival. "About the Festival." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.chestertownteaparty.org/

- The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. "Introduction to Colonial African American Life." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.history.org/Almanack/people/african/

aaintro.cfm - Encyclopædia Britannica. "Cecilius Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore of Baltimore." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/51041/Cecilius-Calvert-2nd-Baron-Baltimore-of-Baltimore

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Charles I." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/106686/Charles-I

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Daniel Dulany." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/173329/Daniel-Dulany

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/51047/George-Calvert-1st-Baron-Baltimore

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "History, Colonial America to 1763." Accessed 6/6/19. https://www.britannica.com/place/United-States/History

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "John Carroll." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/97085/John-Carroll

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Leonard Calvert." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/90241/Leonard-Calvert

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Maryland." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/367594/Maryland

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Saint Clements Island." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/516933/Saint-Clements-Island

- Encyclopedia Virginia. "Margaret Brent > Ingle's Rebellion." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Brent_Margaret_ca_1601-1671#its2

- Enoch Pratt Free Library. "African Americans in Maryland: Firsts and Facts." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.prattlibrary.org/locations/afam/index.aspx?id=4448

- Historic St. Mary's City. "The Colonial Kids' Guide to St. Mary's City." Accessed 6/6/19. https://www.hsmcdigshistory.org/pdf/Colonial-Kids-Guide.pdf

- Historic St. Mary's City. "Maryland State History." Accessed 6/6/19. https://hsmcdigshistory.org/research/history/

- Historic St. Mary's City. "Narrative of a Voyage to Maryland." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.digshistory.org/pdf/Voyage-Narrative.pdf

- History of the USA. Converted from Henry William Elson's History of the United States of America. The MacMillan Company, NY, 1904. "Maryland." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.usahistory.info/southern/Maryland.html

- Independence Hall Association. "Charles Carroll of Carrollton." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.ushistory.org/declaration/signers/carroll.htm

- Independence Hall Association. "Samuel Chase." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.ushistory.org/declaration/signers/chase.htm

- Independence Hall Association. "Thomas Stone." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.ushistory.org/declaration/signers/stone.htm

- Independence Hall Association. "William Paca." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.ushistory.org/declaration/signers/paca.htm

- Infoplease. "George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.infoplease.com/encyclopedia/people/calvert-george-1st-baron-baltimore.html

- Infoplease. "Maryland." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.infoplease.com/encyclopedia/us/maryland-history.html

- Infoplease. "Test Act." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.infoplease.com/encyclopedia/history/test-act.html

- Infoplease. "Thomas Stone." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.infoplease.com/biography/us/congress/stone-thomas.html

- Kent Island Heritage Society. "History of Kent Island." Accessed 6/6/19. https://www.kentislandheritagesociety.org/kent-island-history/

- Library of Congress. "Benjamin Banneker Historical Park and Museum." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.americaslibrary.gov/es/md/es_md_banneker_1.html

- Library of Congress. "British Reforms and Colonial Resistance, 1763–1766." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/

presentationsandactivities/presentations/timeline/amrev/britref/ - Library of Congress. "Chestertown Tea Party Festival." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.americaslibrary.gov/es/md/es_md_tea_1.html

- Library of Congress. "Maryland." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.americaslibrary.gov/es/md/es_md_subj.html

- Library of Congress. "Mathematician and Astronomer Benjamin Banneker Was Born November 9, 1731." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.americaslibrary.gov/jb/

colonial/jb_colonial_banneker_1.html - Library of Congress. "Today in History: November 9." Accessed 6/6/19. http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/today/nov09.html

- Lonang Institute. "Constitution of Maryland, November 3, 1776." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.lonang.com/exlibris/organic/1776-mdr.htm

- The Lower Eastern Shore Heritage Council. "Native American Heritage: They Passed This Way." Accessed 6/6/19. http://lowershoreheritage.org/index.php/LESHeritage/interests_article/native-american-heritage/

- The Mariners' Museum. "The Colonial Period, 1607–1780." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.marinersmuseum.org/sites/micro/cbhf/economy/cbe001.html

- Maryland Department of Natural Resources. "Fort Frederick State Park." Accessed 6/6/19. https://dnr.state.md.us/publiclands/Pages/western/fortfrederick.aspx

- Maryland Department of Natural Resources. "St. Clements Island State Park." Accessed 6/6/19. https://dnr.state.md.us/publiclands/Pages/southern/stclements.aspx

- Maryland Historical Society. "Harwood Mason-Dixon Line Marker Collection." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.mdhs.org/findingaid/harwood-mason-dixon-line-marker-collection-pp37

- Maryland Humanities Council. "The Maryland History and Culture Bibliography." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.lib.umd.edu/dcr/collections/mdhc/results.php

- Maryland Office of Tourism. "Central Maryland." Accessed 6/6/19. http://visitmaryland.org/Central/Pages/Destinations.aspx

- Maryland Public Television. "Captain Henry Fleet." Accessed 6/6/19. http://mdroots.thinkport.org/library/henryfleet.asp

- Maryland Public Television. "Cecil (Cecilius) Calvert, Second Lord Baltimore." Accessed 6/6/19. http://mdroots.thinkport.org/library/cecilcalvert.asp

- Maryland Public Television. "Exploring Maryland's Roots." Accessed 6/6/19. http://mdroots.thinkport.org/

- Maryland Public Television. "Frequently Asked Questions: The Colony Grows." Accessed 6/6/19. http://mdroots.thinkport.org/library/faqs_grows.asp

- Maryland Public Television. "Gov. William Stone and Verlinda Stone." Accessed 6/6/19. http://mdroots.thinkport.org/library/williamverlindastone.asp

- Maryland Public Television. "Margaret Brent." Accessed 6/6/19. http://mdroots.thinkport.org/library/margaretbrent.asp

- Maryland Public Television. "Mathias de Sousa." Accessed 6/6/19. http://mdroots.thinkport.org/library/mathiasdesousa.asp

- Maryland Public Television. "Slavery Comes to Early Maryland: A Brief Look," by David Taft Terry. Accessed 6/6/19. http://mdroots.thinkport.org/interactives/

slaverytimeline/slavery.pdf - Maryland Public Television. "William Claiborne." Accessed 6/6/19. http://mdroots.thinkport.org/library/williamclaiborne.asp

- Maryland the Seventh State. "The French and India War," by John T. Marck. Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.marylandtheseventhstate.com/article1076.html

- Maryland State Archives. "A Declaration of The Lord Baltemore's Plantation in

Mary-land." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.msa.md.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/

sc2900/sc2908/000001/000550/html/am550--7.html - Maryland State Archives. "A Relation of the Successefull Beginning of the Lord Baltemore's Plantation in Mary-land." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.msa.md.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc2900/sc2908/000001/000551/

html/am551--8.html - Maryland State Archives. "An Act Concerning Religion, April 21, 1649," by Edward C. Papenfuse, Jr. Accessed 6/6/19. http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/speccol/sc2200/

sc2221/000025/html/toleration.html - Maryland State Archives. "Charles County, Maryland." Accessed 6/6/19. http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/mdmanual/36loc/ch/html/ch.html

- Maryland State Archives. "Citizen Legislators and Toleration," by Dr. Edward C. Papenfuse, Jr. Accessed 6/6/19. http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/stagser/s1259/

123/html/mdayremarks.html - Maryland State Archives. "Constitution of Maryland: Declaration of Rights." Accessed 6/6/19. http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/mdmanual/43const/

html/00dec.html - Maryland State Archives. "Margaret Brent: A Brief History." Accessed 6/6/19. http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/002100/002177/html/

mbrent2.html - Maryland State Archives. "Maryland at a Glance: Historical Chronology:

1600 - 1699." Accessed 6/6/19. http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/mdmanual/

01glance/chron/html/chron16.html - Maryland State Archives. "Maryland at a Glance: Historical Chronology:

1700 - 1799." Accessed 6/6/19. http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/mdmanual/

01glance/chron/html/chron17.html - Maryland State Archives. "Maryland at a Glance: Holidays: Maryland Day." Accessed 6/6/19. http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/mdmanual/01glance/

html/mday.html - Maryland State Archives. "The Burning of the Peggy Stewart." Accessed 6/6/19. http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/speccol/sc1500/sc1545/001100/001111/text/

label.html - Maryland State Archives. "The Planting of the Colony of Maryland." Accessed 6/6/19. http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/speccol/sc1500/sc1545/001100/001125/

html/label.html - Maryland State Archives. "What's in a Name? Why Should We Remember? The Liberty Tree on St. John's College Campus, Annapolis, Maryland," by Edward C. Papenfuse. Accessed 6/6/19. http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/educ/html/

liberty.html - McGovern, Thomas J. "It Is the Mass that Matters." Christendom Awake. Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.christendom-awake.org/pages/mcgovern/penallaws.htm

- Nanticoke Indian Association, Inc. "History." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.nanticokeindians.org/page/history

- National Park Service. "All Aboard for Cumberland." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/cumberland/

- National Park Service. "The Algonquian-Speaking Indians of Maryland," by Wayne E. Clark. Accessed 6/6/19. https://studylib.net/doc/8376936/the-algonquian-speaking-indians-of-maryland

- Our Country, Vol. 1. "Sir George Calvert, Lord Baltimore." Public Bookshelf. Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.publicbookshelf.com/public_html/

Our_Country_Vol_1/sirgeorge_ej.html - Pepperdine University. "Maryland Act Concerning Religion." Accessed 6/6/19. https://publicpolicy.pepperdine.edu/academics/research/faculty-research/american-founding/founding-documents/md_act_con.htm

- Prince George's County Historical Society. "Hall of Fame Inductees." Accessed 6/6/19. http://pghistory.org/main/hall-of-fame/

- Prince George's County Historical Society. "The Tobacco County." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.pghistory.org/PG/PG300/tobacounty.html

- The Royal Household. "Henry VIII." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.royal.gov.uk/HistoryoftheMonarchy/KingsandQueensofEngland/

TheTudors/HenryVIII.aspx - Secretary of State, Statehouse, Annapolis, MD. "Maryland History Timeline." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.mdkidspage.org/Timeline.htm

- Southern Maryland Online. "St. Clements Island — Potomac River Museum." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.somd.com/Detailed/1494.php

- St. Mary's County Government. "Welcome to St. Mary's County." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.co.saint-marys.md.us/

- United States Genealogical Network. "The Province of Maryland." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.usgennet.org/usa/md/state/

- University of Maryland Baltimore County. "Was the Stamp Act Fair?" Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.umbc.edu/che/tahlessons/lessondisplay.php?lesson=39

- University of Maryland Baltimore County. "Who Burned the Peggy Stewart?" Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.umbc.edu/che/tahlessons/lessondisplay.php?lesson=29

- U.S. National Archives. "Bill of Rights." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/bill_of_rights_transcript.html

- U.S. National Archives. "Declaration of Independence: A History." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/declaration_history.html

- U.S. National Archives. "Declaration of Independence: The Signer's Gallery." Accessed 6/6/19. http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/

declaration_signers_gallery.html - Visit Baltimore. "African American History and Culture." Accessed 6/6/19. http://baltimore.org/multicultural/black-history

- Yale University, Avalon Project. "Maryland Toleration Act; September 21, 1649." Accessed 6/6/19. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/

maryland_toleration.asp - Yale University, Avalon Project. "The Charter of Maryland: 1632." Accessed 6/6/19. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/ma01.asp

Maryland | Image Credits

- Maryland and the Chesapeake Region, 1634–1660 | Adams, James T., Ed. Atlas of American History. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1943. (p. 19)

- George Calvert | Artist: Daniel Mytens, c. 1625; Wikimedia Commons

- Leonard Calvert | Artist: Florence Mackubin, 1914; Maryland State Archives

- Margaret Brent | Artist: Louis Glanzman, 1976; Maryland State Archives, courtesy of the National Geographic Society

- Cecilius Calvert | Artist: Florence Mackubin, c. 1910; Maryland State Archives

© 2020 Small Planet Communications, Inc. + Terms/Conditions + 300 Brickstone Square, Andover, MA 01810 + (978) 794-2201 + Contact